Bach’s Church Cantatas: Music as Theology in the Lutheran Tradition

A huge amount of Bach's creative output was directly intended for use in the church.

What Were Bach's Church Cantatas?

A cantata is a vocal composition with an instrumental accompaniment. It usually has several movements and involves use of a choir. Cantatas as a musical form became prevalent in Europe during the early 17th century. Composition of cantatas continued through the centuries and are still being written in modern times.

A church cantata is a multi-movement vocal and instrumental work designed to be performed during a church service. During Bach’s tenure in Leipzig (1723–1750), he composed an astonishing number of these works, creating approximately 200 cantatas that survive today, though it’s estimated he may have written as many as 320.

Typical Cantata Structure

A Biblical Text: Often drawn from the Gospel or Epistle reading assigned to that Sunday in the liturgical calendar. As we will see during our series on Bach’s church cantatas over the next year, Bach often followed Luther’s approach, employing Scripture to interpret Scripture.

Chorales: Lutheran hymns that congregants would recognize, serving as spiritual anchors within the cantata. Luther created the chorale to catechize the people through song.

Aria and Recitative Sections: Solo vocal parts that interpreted the scriptural or theological themes of the day, supported by instrumental accompaniment. Often, the text of arias would be poetic, where recitatives would draw on Biblical text.

Opening Chorus and Closing Chorale: The cantata often began with a majestic choral setting and concluded with a harmonized chorale, creating a sense of symmetry.

The cantatas were not standalone performances but integral to the liturgical fabric of the service. They were composed for specific Sundays and feast days, reflecting the themes of the sermon, scripture readings, and hymns. It is likely that Bach consulted with the theologians available to him as he composed, ensuring proper alignment with Scripture and doctrine.

Robin Leaver described Bach’s cantata structure:

“Many cantatas have a similar ground plan. In the opening chorus the problem is stated, that is, the demands of the law; a recitative and aria draw out some of the implications; then, approximately halfway through the cantata, the problem is resolved, that is, the gospel is proclaimed; a note of joy in the gospel is heard in the following aria or arias; and the cantata concludes with the chorale, which underscores the message of the gospel with a statement of faith.”

The Role of Cantatas in the Lutheran Church

In the early 18th century, Lutheranism emphasized the importance of music as a means of communicating theological truths. Martin Luther himself had elevated the role of music in worship, famously stating, “Next to the Word of God, the noble art of music is the greatest treasure in the world.”

Friedrich Smend said “Bach’s cantatas are not intended to be works of music or art on their own, but to carry on, by their own means, the work of Luther, the preaching of the Word and nothing but the Word.”

Enhancing the Worship Experience

Bach’s cantatas served as theological reflections, turning abstract doctrines into deeply emotional experiences. By weaving together scripture, hymn texts, and poetic librettos, he created works that amplified the spiritual messages of the day. Congregants were not merely spectators; they were participants in a sacred dialogue between text and music.

For example, Cantata BWV 140, Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme ("Sleepers Awake"), written for the 27th Sunday after Trinity, meditates on the parable of the wise and foolish virgins. Its joyful melodies and insistent rhythms embodied the theme of readiness for Christ’s return, encouraging listeners to prepare their hearts.

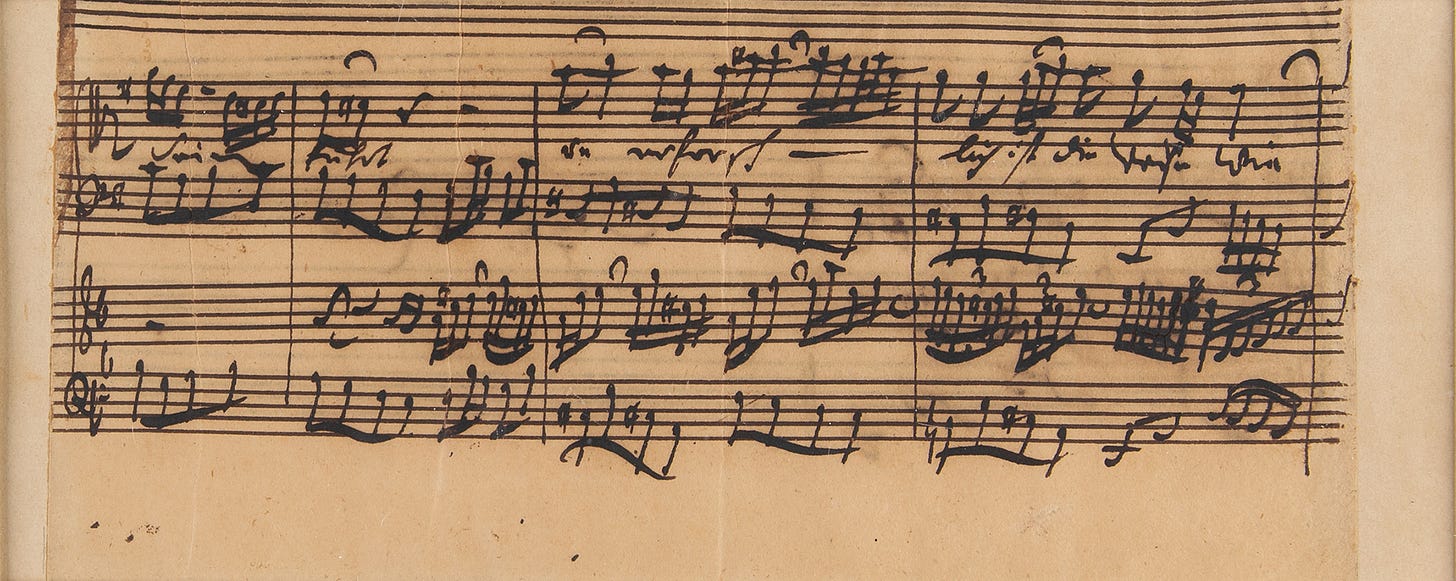

Today, Cantatas are typically performed from start to finish, straight through. That was not necessarily the case in Bach’s church in his day. The Cantata for the given Sunday or festival would have been broken up to match the liturgical need of the service. An example is seen in Bach’s own score of Cantata BWV 61, where he outlined the order of service:

Order of the Divine Service in Leipzig on the First Sunday in Advent: Morning.

1. Preluding.

2. Motet.

3. Preluding on the Kyrie, which is performed throughout in concerted manner [musiziert].

4. Intoning before the altar.

5. Reading of the Epistle.

6. Singing of the Litany.

7. Preluding on [and singing of] the Chorale.

8. Reading of the Gospel.

9. Preluding on [and performance of] the principal music [cantata].

10. Singing of the Creed [Luther’s Credo hymn].

11. The Sermon.

12. After the Sermon, as usual, singing of several verses from the hymnal;

13. Words of Institution [of the Sacrament].

14. Preluding on [and performance of] the Music [probably the second half of the cantata]. And after the same, alternate preluding and the singing of chorales, until the end of the Communion, etc.

Integration with the Liturgical Calendar

Bach’s cantatas were carefully aligned with the Lutheran church year. Each Sunday and feast day had a prescribed set of Scripture readings (the lectionary), which provided the thematic foundation for the cantata. The appointed readings closely align with our current One Year Lectionary.

For instance:

During Advent, Bach’s cantatas often reflected the anticipation of Christ’s coming (Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 62).

At Easter, jubilant works celebrated the Resurrection (Christ lag in Todesbanden, BWV 4).

Bridging Faith and Emotion

One hallmark of Bach’s cantatas is their emotional range, which Bach used to mirror the human experience of faith. In Ich habe genug (BWV 82), a cantata written for the Feast of the Purification of Mary, the baritone aria expresses the soul’s longing for eternal rest. He used compositional devices and harmony to create emotional inflections, adding musical emphasis to the libretto.

Bach, at times, got himself into trouble with the Leipzig authorities by writing music that played on the emotions too much. His Saint Matthew Passion, today seen as one of, if not the greatest of Bach’s compositions, was highly controversial when first performed.

Paul Hofreiter writes about Bach’s use of cantatas this way:

In the music of Bach we do, indeed, find “the word in worship turn into song and hymn.” Such is the case largely because Bach’s faith was rooted in the theology of the Lutheran orthodoxy which “perceived music as an explicato textus - a means of interpreting God’s Word - and as a praedicatio sonora - a resounding sermon.

Why Do Bach's Cantatas Endure?

Bach’s church cantatas continue to captivate audiences worldwide, transcending their original liturgical function. Their enduring appeal lies in:

Musical Complexity and Beauty: Bach’s use of counterpoint, harmony, and melody creates works of unparalleled sophistication.

Theological Depth: These works are rich in scriptural and doctrinal content, far surpassing superficial background music or lifeless accompaniment.

Today, these cantatas are performed in concert halls and churches alike, reminding modern listeners of the profound role that music can play in faith and worship. It is interested to consider what Bach might have thought of this; his church music played to secular audiences divorced from their original intended settings of the Lutheran church.

Conclusion: Bach’s Legacy in the Lutheran Tradition

Johann Sebastian Bach’s church cantatas were more than just music; they were sermons in sound, illuminating the scriptures and touching the hearts of congregants. This continues today, as his music serves as a means of evangelism. Through his compositions, Bach embodied the Lutheran ideal of music as a gift from God.

The profound beauty of Bach’s compositions becomes even more apparent when viewed through the Lutheran lens; recognizing his devotional approach to composition and careful treatment of Holy Scripture.

As we listen to these works today, we are invited to step into the shoes of an 18th-century Leipzig worshiper, experiencing the sacred as Bach intended: through the eegant fusion of Word and music, theology and art.